Industrial Policy Must Include Citizens And Workers

By Werner Raza

Europe's twin transformation needs social conditionalities to prevent corporate capture and build democratic legitimacy.

The green and digital transformations will produce deep changes to our modes of production and consumption, indeed to our entire way of life. Along this transformative journey, some segments of society will profit handsomely, whilst others—particularly large numbers of workers in shrinking industries—will find themselves negatively affected, at least during the transitory period of the next two to three decades. Thus, whatever the specific motivation for industrial policy, to be accepted by societal stakeholders, it must be considered legitimate by those it affects.

Given the fundamental uncertainty of the process and the associated social concerns, sustained political support critically depends upon a positive, if not optimistic, vision of the future. Citizens as well as affected workers will need to be convinced of three essential points: first, that the twin transformation is not only necessary but indeed desirable for their futures; second, that they are genuine stakeholders in this process with a meaningful chance to co-shape its direction; and third, that their aspirations and concerns are taken into serious consideration, ensuring that the distribution of benefits and costs during the transformation remains fair and balanced.

Three pillars of legitimate transformation

These three requirements for a legitimate political approach to managing the twin transformation can be substantiated through three concepts from political theory: hegemony, input legitimacy and output legitimacy. Hegemony, interpreted here in the Gramscian sense, refers to the requirement for a vision of change—or grand narrative—underlying the political management of the twin transformation that succeeds in convincing people and garnering active support from civil society. Such a vision should inspire hope and optimism for a better future, not merely acceptance of inevitable change.

Apart from this ideational element, support at the macro level and particularly at the micro level of the workplace and the household becomes more likely when combined with two further elements. Input legitimacy implies that citizens and workers are given a genuine stake in the process and a meaningful chance to voice their interests and concerns. Output legitimacy entails that the instruments and policies employed actually deliver on the promises of the transformation process, and that the social costs arising along the way are managed in an effective and balanced manner. Input and output legitimacy function as complementary forces. Though the balance between them may shift during different phases of the process, both should be continuously employed to secure and maintain legitimacy.

The violated social contract of public subsidies

Industrial policy interventions come in different forms but can be roughly categorised into three main types: financial transfers (including grants, preferential loans, guarantees and public equity), taxes and tariffs, and regulation (encompassing disciplines and prohibitions). The predominant neoliberal policy framework during the last four decades, as codified for example in European Union competition and state aid rules, by and large displayed a restrictive stance towards public transfers to the private sector. Subsidies needed special justification and were only allowed for a number of specific exemptions, including research and innovation, regional development and particular social purposes. The main economic arguments levelled against subsidisation emphasised competitive distortions, rent-seeking behaviour, and moral hazard—particularly in the case of state-financed corporate bailouts.

At the latest with the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020 and the war in Ukraine since 2022, this state of affairs has markedly changed. Both the EU and most member states have initiated large-scale funding programmes including hefty handouts to private companies. Motivated by the challenges of the twin transformation as well as geopolitical security concerns, large industrial policy programmes have been initiated in many industrialised countries, including the United States, the European Union, China and Japan. These programmes typically target certain strategic sectors, such as semiconductors, green technologies or telecommunications.

The principal rationale for mobilising significant public financial resources for the twin transformation relates to influencing the directionality and speed of private investment against a backdrop of existential threats emanating either from climate change or from geopolitical risks. Targeted areas include but are not limited to the build-up of domestic productive capacity in strategic products like semiconductors, or the fundamental switch to energy production based on renewables. Predominantly, this is not achieved through command-and-control measures, but indirectly by offering the corporate sector financial incentives under the condition that public funds are used to achieve a defined objective within a set timeframe. Thus, ideally, a desired process of change, such as the decarbonisation of the economy, can be catalysed, if not substantially accelerated. In practice, however, monitoring and control regarding success are often lacking, and public authorities frequently do not dispose of effective means to ensure compliance. In other words, whilst carrots are plentiful, sticks remain conspicuously blunt.

From the perspective of democratic legitimacy, the implicit social contract underlying such an industrial policy approach led by an entrepreneurial state is violated by such a state of affairs. Given the required scale and speed of the twin transformation, the necessary adjustment requires a collective effort encompassing all members of political society, with each making their contribution according to their abilities. Adjustment burdens exceeding individual possibilities must be shared throughout the community, in particular by offering public financial support where needed. Receiving public money thus obliges the recipient to honour their part of the implicit social contract. This includes using the money for the defined purpose, in conformity with the respective legal framework conditions, and sharing any benefits eventually accruing from the investment, whether with the direct stakeholders of the company (namely owners and workforce), or with the general public at large (through tax contributions, free licensing of new technical knowledge, and similar mechanisms).

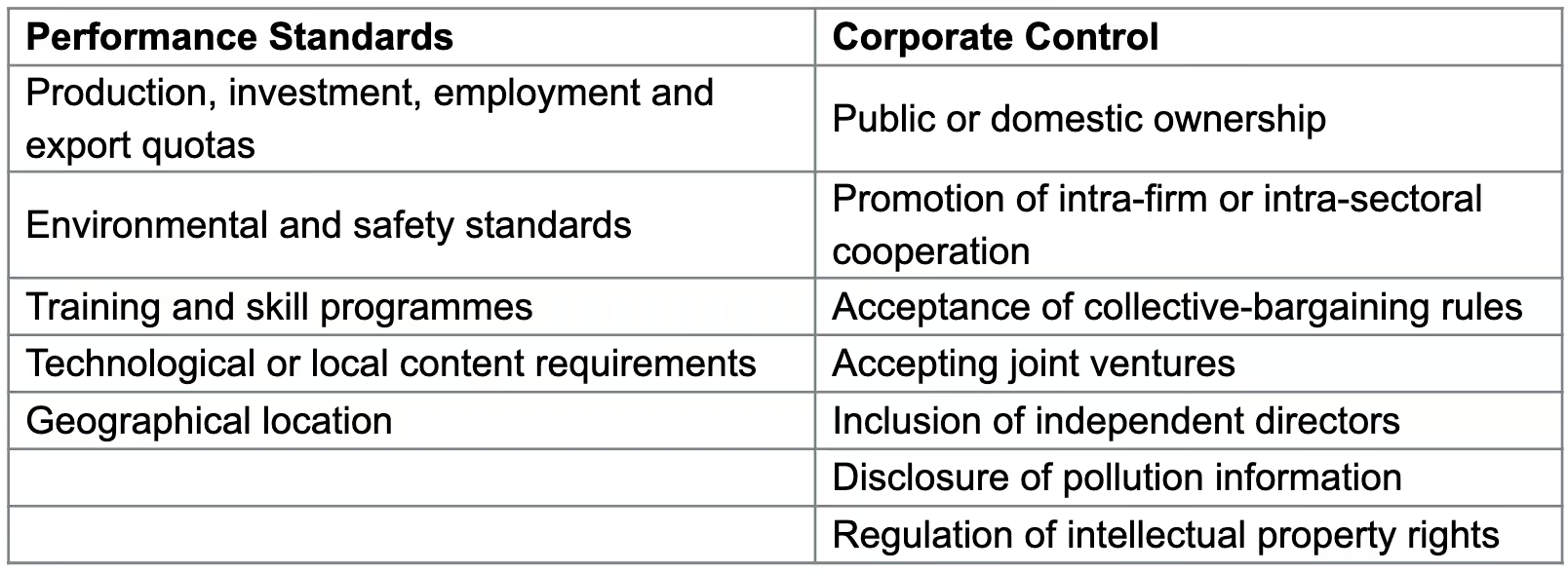

With the government in a liberal democracy acting as the collective agent of society, it bears the obligation to implement such an agreement. This is typically done through a funding contract, which stipulates the conditions under which the beneficiary is entitled to receive the financial transfer. Such conditions may come in multiple forms, including through performance standards—targets to be achieved by the beneficiary relating to production, investment or employment. In addition, process conditions might be employed that oblige the beneficiary to accept or introduce changes to its corporate governance system, for instance public ownership or co-ownership, introduction of collective bargaining, or special transparency or reporting mechanisms (see Table 1 below for a comprehensive overview).

Table 1: Industrial Policy Conditionalities.

Source: author's elaboration, based on Bulfone, Ergen and Maggor (2024)

The crucial role of social conditionalities

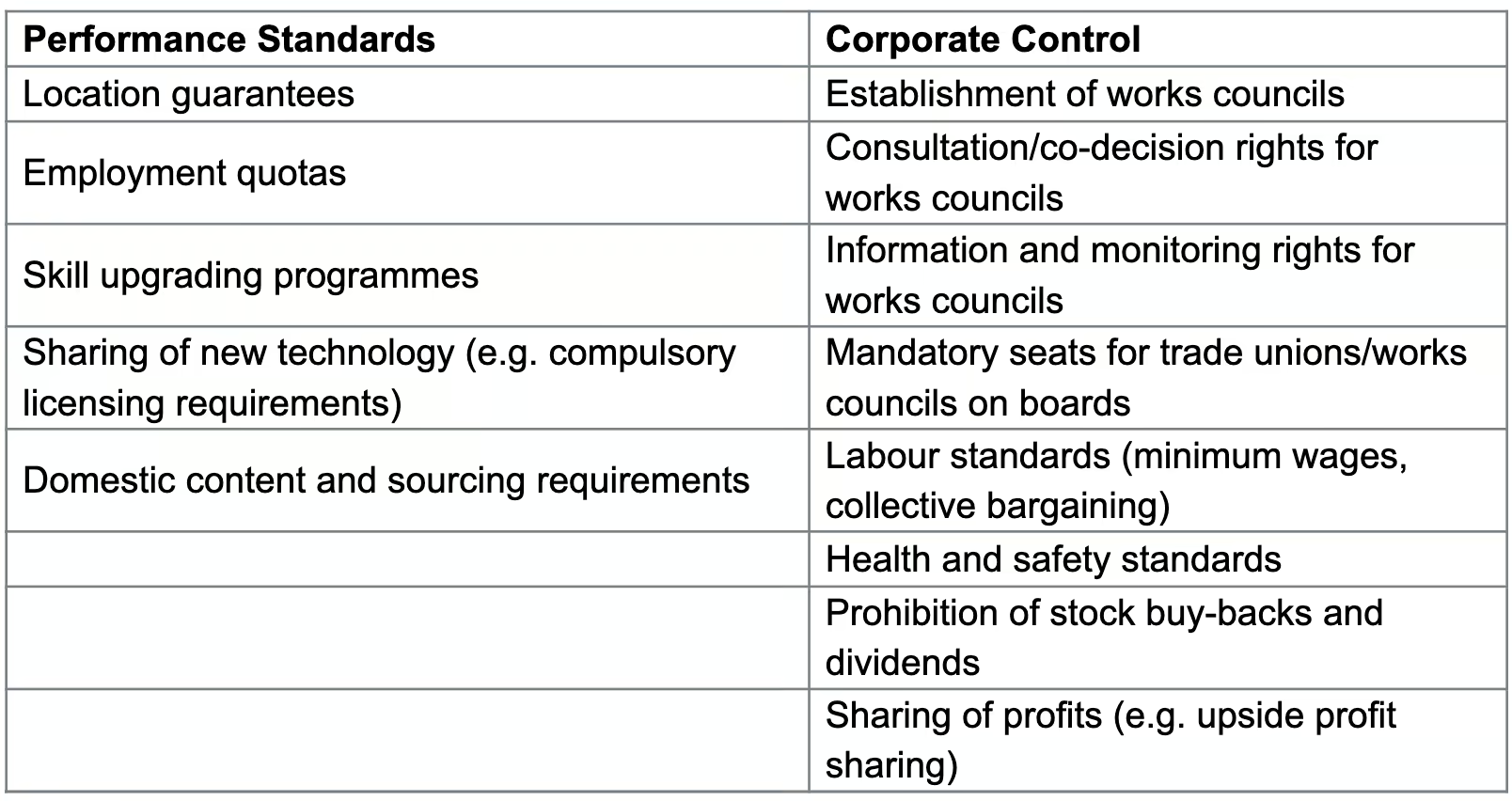

A specific subcategory of particular importance refers to social conditionalities. These include both measures targeting the affected labour force—such as via employment and labour standards, skills acquisition, the establishment of works councils or collective bargaining—and extend to measures that benefit society at large, including the sharing of new technology, the sharing of excess profits, or domestic content requirements (see Table 2 below for a detailed taxonomy).

Table 2: Indicative Taxonomy of Social Conditionalities.

Source: author's elaboration

Whilst there is widespread agreement that the green and digital transformations pose extraordinary challenges that require this collective effort—including the transfer of significant amounts of public money to the private sector—the danger of corporate welfarism is clearly looming in the background. In other words, corporate beneficiaries might see the availability of public money as a windfall opportunity for increasing profits via rent-seeking or moral hazard behaviour, for example by pocketing public money intended for revitalising ailing business activities. In addition, as currently not only the EU but many other countries have set up massive financial support programmes, particularly large transnational corporations might try to play governments off against each other to extract the highest possible subsidy.

The scholarly literature on corporate welfarism emphasises that the privatisation of many state-led activities (such as public services) during the neoliberal period has resulted in a marked shift of structural power in favour of the corporate sector. Unfortunately, in many respects the state has lost its capacity to directly take care of certain activities, and in fact depends on the private sector to perform such essential tasks. This literature thus warns against the prevailing view that the return of industrial policy should be interpreted as a sign of renewed state power. Instead, the prevalence—or notable absence—of strong conditionalities attached to financial handouts to private firms should be the indicator upon the basis of which to assess the actual power balance between the state and private capital.

Learning from transatlantic differences

Preliminary comparative assessments of conditionality policies of the EU and other countries, in particular the United States, highlight the following aspects that merit particular attention. First, the US, notably under the Biden administration, has been markedly more proactive in including social conditionalities than the EU, using a wide array of different instruments (see here and here for detailed analyses). Second, coalition-building, in particular with trade unions and civil society organisations, combined with a broadly shared motivation—in the US primarily the geopolitical threat of China to American supremacy—have been critical for successful implementation and monitoring of these conditions. Third, government monitoring and enforcement during implementation proves difficult due to capacity constraints and lacking access to information, but is significantly facilitated by including monitoring provisions that grant corporate stakeholders, such as works councils and trade unions, access to information. Fourth, the legal room to define and include conditionalities into funding agreements is relatively wide, even under EU competition and state aid law. It is ultimately constrained only by fundamental constitutional rights, such as the protection of private property (see analyses here and here).

To the extent that information is publicly available, until now the EU and member states have used conditionalities only selectively, and notably not with a focus on social conditionalities. Examples include, amongst others, conditionalities to prevent fraud within the framework of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). In the Microelectronics Important Project of Common European Interest (IPCEI), a "claw-back" profit-sharing mechanism was introduced, under which companies may be required to redistribute extra profits obtained as a result of EU funding. In the case of a supply chain crisis, the Commission can require semiconductor companies that have received financial support under the EU Chips Act to share information about their production capacities and, if necessary, to prioritise domestic orders for critical products. If companies do not comply with these requirements, the Commission can impose fines or other sanctions. Within the framework of the European Defence Fund, access to funding is restricted to companies established in at least two EU member states, or associated members part of the European Economic Area. Intellectual property rights resulting from funded projects should not be controlled by any third countries or third-country entities. Otherwise, the Commission can claw back the initial funding.

Various reasons are proposed in the literature as to why the conditionality regime in the EU appears relatively weak (see analyses here, here and here). Amongst them are, first, the lack of financial power of the EU and its dependency on member states to extend funds. Second, administrative capacity constraints exist both at EU level, but particularly at the level of member states where implementation actually occurs. Third, a comparatively weak security disposition prevails, including opposing views on the nature and extent of the "China threat".

With respect to the notably low profile of social conditionalities, the already relatively high level of labour and social standards in the EU, as well as the systematic exclusion of trade unions from industrial policymaking in the EU, serve as the main explanations. In marked contrast to the US, where trade unions have played an important role in co-designing social conditionalities, and thus have put considerable pressure upon the Biden administration to include them, the calls of European trade unions to introduce stronger social conditionalities have been mostly ignored by the Commission as well as member state governments.

Securing democratic legitimacy through social inclusion

By way of conclusion, conditionalities, including in particular social conditionalities, represent a central mechanism for guaranteeing the desired directionality of investment, as well as for making certain that the social benefits generated by public support are widely shared across society. Weak or non-existent conditionality indeed invites the kind of adverse behaviour emphasised in the economics literature, such as rent-seeking, moral hazard or anti-competitive behaviour. Given the relatively weak bargaining position of many EU institutions as well as governments vis-à-vis the corporate sector, and in particular large transnational corporations, it is precisely through conditionalities that the public purpose of financial transfers, and thus their output legitimacy, can be safeguarded.

But social conditionalities also offer the opportunity for achieving a higher degree of input legitimacy. A more inclusive approach to industrial policy, one that gives workers and trade unions a meaningful voice in the process, will at the end of the day mobilise broader societal support for the twin transformation. Last but not least, this broader social support will increase the autonomy of policymakers at national and EU level in pursuing industrial policy even against the resistance of specific social groups. Without such democratic foundations, Europe's industrial policy risks becoming yet another exercise in corporate capture rather than the collective endeavour our shared future demands.